Think Inside The Box

Origin story: Think Inside The Box was developed in 2004 over a whole bunch of lunches with Todd Theodore, a really smart guy I worked with at Nationwide (he now works at Battelle). I initially conceived it as a potential solution for common problems we were experiencing in getting creative work done. Todd and I then discussed and refined it over several months.

Here's the problems we were trying to address:

• People thought that giving someone complete and total freedom the best thing for not stepping on creative toes.

• People thought that telling everyone to “think outside the box” was how you found the good ideas.

• Designers were complaining about restrictive managers/clients, and managers/clients were complaining about impractical designers.

• Projects were poorly defined, so solutions were off the mark, so the project goals were defined only a little better, so the changes were still off the mark a bit, etc. The beginning of the project was the worst part, and it affected everything else.

• Presentations were a free-for-all, and rarely pointed back to the design problem that was presented. This often resulted in sweeping design changes, and now with less time to finish the work.

We wanted a process that either side (creatives and clients) could use to get better results and make the work more enjoyable.

Here's the problems we were trying to address:

• People thought that giving someone complete and total freedom the best thing for not stepping on creative toes.

• People thought that telling everyone to “think outside the box” was how you found the good ideas.

• Designers were complaining about restrictive managers/clients, and managers/clients were complaining about impractical designers.

• Projects were poorly defined, so solutions were off the mark, so the project goals were defined only a little better, so the changes were still off the mark a bit, etc. The beginning of the project was the worst part, and it affected everything else.

• Presentations were a free-for-all, and rarely pointed back to the design problem that was presented. This often resulted in sweeping design changes, and now with less time to finish the work.

We wanted a process that either side (creatives and clients) could use to get better results and make the work more enjoyable.

How does it work?

Here’s the big idea, and it’s a paradox: the better defined a problem's limits, the better our creative minds can work.

Every problem has limits, and eventually you will find them out. It’s just much easier when you establish them up front, instead of finding them out after you have crossed them and now have to pull back.

True creative thinking requires trust. The creative mind needs to know where the edges of the sandbox are, because even if you can’t see them, you know they are there. For example, what’s your reaction to “it’s wide open - do whatever you want”? If you're like me, you sense that the wild idea you come up with will be outside the boundaries. “Oh, well that really wasn’t what I had in mind...”.

Limits provide focus and save time. You can pursue your ideas with abandon because you know they will work and you know you aren’t wasting time going after something blue when it has to match something red.

The “box” is the combination of the project limits – goal, audience, time, $/equipment/space, quality, people resources, and history. Every usable solution must fit within the limits, or it isn’t a usable solution.

The biggest two problems I've found are:

For example, here's an example of a typical problem/solution conversation between a Project Manager and a Designer.

THING1: "I need a canoe."

THING2: "OK, here's a canoe."

A well-defined but very small box, producing an acceptable, but uncreative solution. Some problems are fine this way, but not ones where creative solutions are the goal. Let's try it another way.

THING1: "I need a canoe, but I need you to think 'outside the box'"

THING2: "OK, what about this feathered pink one here?"

THING1: "What? No, I don’t like pink. And what's with the feathers?”

A promise of a bigger box, but the unfocused call for creativity doesn't give the creative thinking much traction or a target. It just becomes a random guess, and likely to miss. One more try.

THING1: "I need a canoe, and I’m looking for some creative options."

THING2: "OK, let me ask you a few questions first. Will any boat do? Are you trying to go down the river, or just cross it?"

THING1: "Well, I guess any boat would do, but now that you mention it, I guess I am just trying to get across the river."

Ask a few simple questions, and the box suddenly gets not just clearer, but a whole lot bigger. The solutions could now include bridges, planes, scuba gear and catapults. More (and better questions) are needed up front.

So, that’s the basic idea of Think Inside The Box. Challenging and defining limitations by asking a few simple questions up front can create volumes of creative space within which to think. And, the solutions will be relevant and usable because they will be within those limitations. It works for the clients, and it works for the creatives. It builds trust in the creative process and in each other.

Every problem has limits, and eventually you will find them out. It’s just much easier when you establish them up front, instead of finding them out after you have crossed them and now have to pull back.

True creative thinking requires trust. The creative mind needs to know where the edges of the sandbox are, because even if you can’t see them, you know they are there. For example, what’s your reaction to “it’s wide open - do whatever you want”? If you're like me, you sense that the wild idea you come up with will be outside the boundaries. “Oh, well that really wasn’t what I had in mind...”.

Limits provide focus and save time. You can pursue your ideas with abandon because you know they will work and you know you aren’t wasting time going after something blue when it has to match something red.

The “box” is the combination of the project limits – goal, audience, time, $/equipment/space, quality, people resources, and history. Every usable solution must fit within the limits, or it isn’t a usable solution.

The biggest two problems I've found are:

- People don’t get the limits out in the open for everyone to see up front, and

- They almost always make the limits more restrictive than necessary – they build their boxes too small.

For example, here's an example of a typical problem/solution conversation between a Project Manager and a Designer.

THING1: "I need a canoe."

THING2: "OK, here's a canoe."

A well-defined but very small box, producing an acceptable, but uncreative solution. Some problems are fine this way, but not ones where creative solutions are the goal. Let's try it another way.

THING1: "I need a canoe, but I need you to think 'outside the box'"

THING2: "OK, what about this feathered pink one here?"

THING1: "What? No, I don’t like pink. And what's with the feathers?”

A promise of a bigger box, but the unfocused call for creativity doesn't give the creative thinking much traction or a target. It just becomes a random guess, and likely to miss. One more try.

THING1: "I need a canoe, and I’m looking for some creative options."

THING2: "OK, let me ask you a few questions first. Will any boat do? Are you trying to go down the river, or just cross it?"

THING1: "Well, I guess any boat would do, but now that you mention it, I guess I am just trying to get across the river."

Ask a few simple questions, and the box suddenly gets not just clearer, but a whole lot bigger. The solutions could now include bridges, planes, scuba gear and catapults. More (and better questions) are needed up front.

So, that’s the basic idea of Think Inside The Box. Challenging and defining limitations by asking a few simple questions up front can create volumes of creative space within which to think. And, the solutions will be relevant and usable because they will be within those limitations. It works for the clients, and it works for the creatives. It builds trust in the creative process and in each other.

What are the steps?

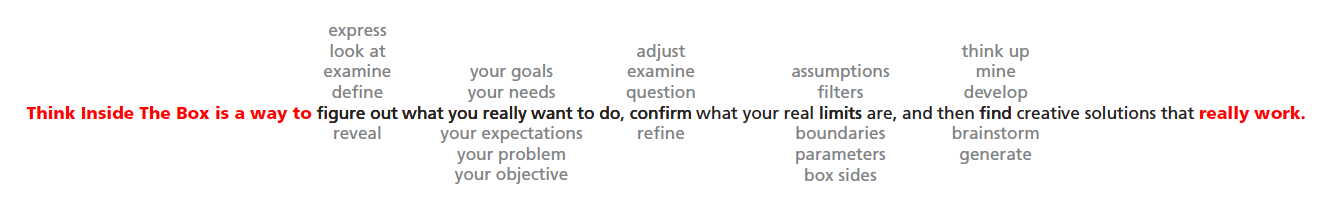

Here’s the TITB four steps:

• BUILD the box by getting all the expectations, limitations, biases and requirements out in the open.

• EXPAND the box by asking good questions that challenge the assumptions inherent in the expectations, limitations, biases and requirements. Most likely, some sides will move, and some won’t.

• THINK creatively inside the box using your own natural abilities in combination with one of the tools like A.R.C., mindmapping, my idea grid, Osborne’s brainstorming rules, or senectics.

• COMPARE the ideas to the limits of the box, and adjust accordingly by either expanding the box or contracting the idea until the creative solution fits. This is how presenting creative ideas should be done. Show why your solution fits the agreed-upon box. Then, it will be much more likely that your solution is approved, or at least recognized as thoughtful and valid even if it isn’t chosen. If it fits, and they don’t like it, then it’s likely that the box was missing some details or had something defined incorrectly, and that is a shared responsibility. That’s a much better position to be in than “your design doesn’t work”.

• BUILD the box by getting all the expectations, limitations, biases and requirements out in the open.

• EXPAND the box by asking good questions that challenge the assumptions inherent in the expectations, limitations, biases and requirements. Most likely, some sides will move, and some won’t.

• THINK creatively inside the box using your own natural abilities in combination with one of the tools like A.R.C., mindmapping, my idea grid, Osborne’s brainstorming rules, or senectics.

• COMPARE the ideas to the limits of the box, and adjust accordingly by either expanding the box or contracting the idea until the creative solution fits. This is how presenting creative ideas should be done. Show why your solution fits the agreed-upon box. Then, it will be much more likely that your solution is approved, or at least recognized as thoughtful and valid even if it isn’t chosen. If it fits, and they don’t like it, then it’s likely that the box was missing some details or had something defined incorrectly, and that is a shared responsibility. That’s a much better position to be in than “your design doesn’t work”.

OK, so that’s a lot of stuff, but I think the concept should be pretty clear. I just think it can be a much less stressful way to work and live. We tend to figure out our boundaries by violating them, rather than agreeing on them up front.

Why hasn't this been published yet?

I have a half-day workshop mostly developed, but never created the opportunity to conduct it. I also had a couple of small books planned, like TITB for creatives, TITB for clients, TITB for personal brainstorming, even TITB for relationships. It will happen...